I was thinking the other day that I had neglected to recommend the great show at the Whitney Museum of paintings by Charles Burchfield. It is up until October 17th and is really worthwhile seeing. The exhibition was curated by Robert Gober and named "Heat Waves in a Swamp," from the title of a Burchfield work. (Deborah Barlow at Slow Muse wrote a very insightful review of the show that you may want to compare with this more biographically-oriented take on it.)

|

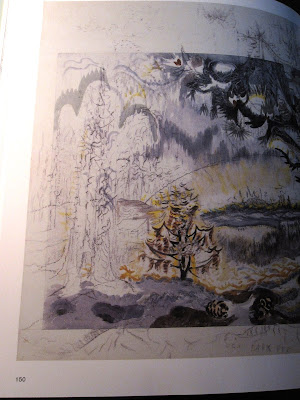

| Charles Burchfield, "An April Mood," 1946-55, Watercolor and charcoal on joined paper, 40 x 54 inches. |

"I like to think of myself--as an artist--as being in a nondescript swamp, up to my knees in mire, painting the vital beauty I see there, in my own way, not caring a damn about tradition, or anyone's opinion."

Charles Burchfield, February 8, 1938

If you are familiar with the work of Robert Gober, you might wonder how and why he would invest himself in the endless time that curating a show takes when his work is so totally unlike Burchfield's. This assumes that artists only admire work that is like their own, and that is a false assumption. Still, while Burchfield totally immersed himself in Nature to the point of finding a Transcendental presence in it, there is a dark and brooding sensibility to his work. I find it slightly scary - there are so many marks and so much going on and the relative sizes of things are not always those observed in reality. You are always aware in his work of the unknown stuff underneath it all--the muck of decay and the leeches in the murky water--in the midst of all the burgeoning growth and life in the swamp. Perhaps this darkness and fear are what attracts Gober.

Whatever it is, Gober suggested the show to Ann Philbin, Director of the Hammer Museum (evidentally a personal friend of Gober's even before this show), and did a fabulous job with "Heat Waves in a Swamp" in conjunction with Cynthia Burlingham, Deputy Director of Collections at the Hammer. The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles opened the exhibition, and it then traveled to the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, and ultimately to the Whitney. The show fills the entire fourth floor of the Whitney and the galleries are arranged chronologically "with each room representing a distinct phase of Burchfield's life and work," as Gober notes in the catalogue

(Slight tangent)

By the way, I liked the show so much that I bought the catalogue (about $50) after looking over a fairly large selection of other books about Burchfield on display at the Whitney. I recommend it and I have taken some photos from it to post here because the Whitney does not allow photography. (And you know how much I love that!)

|

| Cover of the catalogue |

|

| Original Burchfield drawing of camouflage from his stint in the U.S. Army camouflage section 1918-19 |

Back to the show (and the bio)

Charles E. Burchfield, April 9, 1893 - January 10, 1967, was born in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio. His father died when Burchfield was four and a half years old. Burchfield's mother moved back to her hometown of Salem, Ohio with her six children to a house where Burchfield lived until age 28. He began drawing and painting at a very young age and was his high school valedictorian in 1911.Many of his early works were completed while living in this house. He graduated from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1916, at age 23, won a scholarship to study in New York but quit after one class. He began studying on his own by painting and drawing continuously. The work of Hokusai was an early influence. (Be sure to click on photos because they will open really large.)

|

| "Autumnal Fantasy," 1916-44. Watercolor on paper, 39 x 54 inches. |

Wikipedia says that half of his lifetime output of paintings was produced while living in Salem from 1915 to 1917. Later in life he came to regard 1917 as his "Golden Year." Gober says that Burchfield made hundreds of watercolors during 1916-18, often several works of the same subject from different vantage points. (Note how he animates his portrayals of nature by painting sound waves and movements of birds, insects, animals and telegraph wires.)

|

| "Song of the Telegraph," 1917-52. Watercolor on paper, 34 x 53 inches. |

In 1921 Burchfield moved to Buffalo, NY, where he was employed as a designer by the H.M. Birge wallpaper company. In 1922 he married Bertha Kenreich and they produced five children by 1928, settling in the town of Gardenville, NY, near West Seneca, where Burchfield lived with Bertha for the remainder of his life. From 1929 on, when he left the employ of H. M. Birge, Burchfield made his living from his art.

|

| "Sunflowers" wallpaper design, 1921, watercolor and graphite on paper. |

|

| Some of Burchfield's doodles. He drew constantly. |

Burchfield was able to sell his work from the beginning of his career and received recognition early on. In 1930 he had The first one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, following its opening exhibition of work by Cezanne, Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh! (I found it amazing that his work should become so little known or widely disregarded after this unbelievably auspicious start. How soon they forget!)*

|

| April 1930 exhibition catalogue for 27 of Burchfield's works. Over half of them were located for the Hammer show. |

|

| A household name |

|

| A page spread from Burchfield's scrapbook of reviews and notices. |

Watercolor as a medium

The most striking thing about this exhibition to me was the size of the work and that the work looked like no watercolors I had ever seen. The catalogue has an essay by Cynthia Burlingham about why Burchfield chose watercolor as his medium. She traces the history of watercolor, its popularity in different periods and its use by painting masters such as Turner, Sargent, Cezanne and Homer. During the 1910s and 1920s there was a group of innovative American artists who used watercolor as their primary medium including Maurice Prendergast, Demuth, Marin, Hopper and O'Keefe. Burchfield preferred it because of his ease with it from use "since the first grade", its speed and portability for working outdoors and because he could easily layer it on heavy paper without a lengthy wait for drying. He used both transparent and opaque watercolors and added charcoal, crayon, ink and graphite. One thing that Burlingham notes about Burchfield is that he made a conscious effort to submit his work for exhibitions that were not limited to watercolor, thereby insuring that his work was regarded on its own merits and not limited by the medium.

Expansions and Enlargements

If you look back at the dates on the first two paintings under "Back to the Show" above, you will note that they range from 1916-44 and 1917-52. How, you may ask, could someone work on a watercolor for that long? The answer is that when Burchfield looked back on the period of 1916-1918 in his work, he thought that during that time he had:

"The courage to see nature with the great graphic shorthand of youth" - May 15, 1922

He regarded that early work as a great beginning but thought that the works needed to be enlarged to reach their potential.

|

| 1942 plan for enlargement of a 1918 painting, The Red Pool, that was never completed. |

Burchfield used this expansion technique on works dating back to the Golden Year and on pieces begun much later in his life. As someone who can't resist changing work when I come anywhere near it again with a brush in my hand, I find it incredible that he was able to carry out the enlargement of these works so much later in his life without completely remaking them. The process was evidentally not as simple as it might appear, however. Gober says that he made many drawings of possible resolutions before he settled on the final choice.

|

| "Two Ravines," 1934-43. Watercolor on paper, 36 1/2 x 61 1/8 inches |

|

| "Dawn of Spring," ca. 1960s. Watercolor, charcoal and white chalk on joined paper mounted on board, showing charcoal in areas where Burchfield planned to enlarge it. |

|

| Closeup showing additions drawn in charcoal and chalk. |

There were several paintings in the show similar to the work above with a painting in the center surrounded by charcoal drawing. I loved these pieces. They were very beautiful just as they were and really didn't need to be finished.

|

| "October in the Woods," 1938-63. Watercolor, gouache, chalk, and charcoal on joined papers mounted on cardboard, 45 5/8 x 57 3/4 inches. |

|

| Burchfield kept a journal from the time he was 16 until the end of his life. There are 72 volumes of journals totaling close to 10,000 pages. |

Robert Gober opens the catalogue with two quotes from Charles Burchfield's journals which really illuminate his character.

My first vote today. I voted no on Prohibition because it is a blow at personal liberty.

I voted yes on Woman Suffrage because I know so little about politics myself and I am in no position to say they should not have the vote.

I voted straight Socialist ticket because their principles mean the freedom of humanity from graft and greed. November 3, 1914

(After being hospitalized for major surgery between November 10 and 24, 1955)

Some time perhaps I shall feel more like writing more fully about this agonizing time--but not now....At the height of my pain remembering the little field mouse I mutilated when a boy.

*Not everyone forgot him. Burchfield was included in the Carnegie Institute’s The 1935 International Exhibition of Paintings, in which his painting The Shed in the Swamp(1933-34) was awarded second prize. In December 1936 Life magazine declared him one of America’s ten greatest painters in its article “Burchfield’s America.”

In 1940 the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University held Exhibition of Water Colors by Charles Burchfield. Over the next fifty years there were significant exhibitions featuring his work including The Drawings of Charles E. Burchfield at the Cleveland Museum of Art, a retrospective organized in 1956 by The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ Paintings by Charles Burchfield in 1964. His artistic achievement was further honored with the creation of the Charles Burchfield Center at Buffalo State College on December 9, 1966, a month before his death on January 11, 1967.

In 1984 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York curated the exhibition Charles Burchfield, followed in 1986 by the Boston Athenaeum’s An American Visionary: Watercolors and Drawings by Charles E. Burchfield. Charles E. Burchfield: The Sacred Woods was on view at the Drawing Center in New York in 1993, and in 1997 the Columbus Museum of Art organized The Paintings of Charles Burchfield: North by Midwest.

In 1940 the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University held Exhibition of Water Colors by Charles Burchfield. Over the next fifty years there were significant exhibitions featuring his work including The Drawings of Charles E. Burchfield at the Cleveland Museum of Art, a retrospective organized in 1956 by The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ Paintings by Charles Burchfield in 1964. His artistic achievement was further honored with the creation of the Charles Burchfield Center at Buffalo State College on December 9, 1966, a month before his death on January 11, 1967.

In 1984 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York curated the exhibition Charles Burchfield, followed in 1986 by the Boston Athenaeum’s An American Visionary: Watercolors and Drawings by Charles E. Burchfield. Charles E. Burchfield: The Sacred Woods was on view at the Drawing Center in New York in 1993, and in 1997 the Columbus Museum of Art organized The Paintings of Charles Burchfield: North by Midwest.

3 comments:

Hi Nancy, I'm ashamed to say that I was unfamiliar with Charles Burchfield. Such interesting paintings --- and quotes! (especially the artist-in-the-swamp, as well as the memory of the mouse). Thank you for sharing. Wendy

this was an awesome review. i enjoyed reading it very much. although i had seen the artist work before, it had been awhile. Visiting museums has an invigorating effect on us, and you have shown that,that can also come thru in a blog!

"...his work was regarded on its own merits and not limited by the medium."

I really take that statement to heart. Thanks for a thoroughly researched and inciteful post....it's a great exhibit!

Post a Comment